Ken Buehler, 73, stands in a garage that doubles as his living room, outside Ferryville, Wis. His hands (callused with dirt, a mainstay under his nails), like his sweatshirt (grey, worn and torn), tell the story of Buehler’s life, a life spent working on the farm, in the factory and grocery store.

“See these hands,” Buehler volunteers to the diverse journalism students who wander in from Milwaukee one night shortly after the presidential election and to whom he chats as if they are long lost kin. “Working hands. I’ve worked all my life. Paid taxes out the yin-yang. And that’s what I want, people working.”

Buehler straddles two states, so he is the perfect person to start this story. He is from Iowa but lives in Wisconsin. He has a big lit up “Vote Trump” sign in the lawn before his garage/house, although the “T” has fallen off one side, and he voted for Donald Trump. He previously voted for President Barack Obama because he thought it was time for an African-American president. He would vote for Michelle Obama. Now he says of the president, though: “He promised the moon and gave you the shaft.”

Enlarge

He’s included his phone number on the Trump sign, although it’s unclear why. In the distant background, churns the major landmark that unites this corner of the Midwest and its idiosyncratic and independent people: The Mississippi River, touching Wisconsin, Iowa, Minnesota and northwestern Illinois. Ferryville, population 174, the closest town to Buehler’s home, is where you cross into Iowa; it’s an almost entirely white Norwegian enclave perched along the Great River Road that still touts a 1939 visit from Crown Prince Olav and Princess Martha. The county it’s in, Crawford, has mostly German heritage.

Ferryville was an anomaly here; it stuck with Hillary Clinton, but in many of the little villages and towns in Crawford County, Wisconsin, people like Buehler flipped their communities to the Republican for the first time since Ronald Reagan in the 1980s. In so doing, they helped throw their state to Trump, and, along with other Midwestern states, the White House.

“I think people just got sick of the same ol’ same ol’ and wanted something changed,” says Larry Lange, 86, a Trump voter who lives in nearby Steuben, Wisconsin. “Like Trump says, what’ve you got to lose? You’re already at the bottom.”

Trump improved on Mitt Romney’s share of the vote in every single community in Crawford, per Clerk of Courts data.

People worry that their votes won’t count but in an election that turned on margins like these (a 22,000-vote margin for Trump in Wisconsin, just over 10,000 votes in Michigan), white rural working class voters like Buehler – the members of the former Obama and Reagan coalitions – helped write the ending. Contributing to Trump’s victory: Lower turnout and enthusiasm for Hillary Clinton in the cities and here, where her voters seemed more likely to just stay home or go third party and, for the first time, voters had to produce an ID. Voter turnout was at a 20-year low.

However, the people who didn’t vote usually confided that they liked Clinton slightly more but hated both candidates and didn’t feel like their vote would change anything anyway. Example: Wisconsinite Jenny Donlon, who wrote in Betty White for president because she thinks White has more knowledge than both Clinton and Trump. Donlon, who thinks the media don’t understand the Heartland or what it’s like to milk a cow, unplugged her television so she didn’t have to hear the media talk about either candidate anymore.

Enlarge

Crawford County, where Buehler and Donlon live, switched from Obama in 2012 to Trump by 25 percentage points. Buehler’s original state, Iowa, dramatically switched from Obama to Trump; 45 minutes away stands Howard County, Iowa, which switched by the most in the nation (42 percent) and just 20 minutes up the road from that is Fillmore County, Minnesota, where the flip was a similar 29 percent. The region flipped to Trump by the highest percentages in the country, although other areas flipped to him in larger aggregate numbers.

These counties, if you look at the map, form a crimson cluster in the heart of the Mississippi River Valley, lands hotly contested by Chief Blackhawk (those wars still echo in place names like Soldier’s Grove) and settled by German and Norwegian immigrants fond of public displays of religion (“Need God?” asks the sign in bright red letters on one house) and who appreciate order and endless hard work. Today, it’s an almost entirely white and homogenous land of dairy farms, abandoned factories, decaying downtowns, canoe landings, and antique shops.

Its people are individualists. You can find people who listen to both Minnesota Public Radio and Rush Limbaugh. One laundromat has hundreds of dolls dangling from its ceiling, and an old man has a rusted-out plane in his garage. Almost to a one, these folks detest government and politicians (and the big media), even though they might both own the local bar and serve as town clerk. They feel very disconnected from the narratives in Washington and obsessed over in New York news studios. They barely mention race unless asked and could care less about Trump’s sex talk and alleged gropes. However, a few let comments slip that are against Muslims, and they’re quite unhappy with unrest in the cities.

Trump? They liked that he was something different, a non-politician and businessman, a change, and taking it to the elites they hate. They hope he improves the economy. And if they couldn’t stomach some of Trump’s rhetoric, a bunch of them voted for Bernie, Mickey Mouse (or their mother or themselves), or just stayed home. One woman in her 80s walking past the library in Mabel, Minnesota insisted she had never voted – ever. Clinton – despite her historic candidacy in a gender sense – seemed like the status quo. That was unacceptable.

“People are getting tired of working; you know, what used to be a 40-hour week, and now it takes 60-80 hours a week,” said Lime Springs Mayor Kevin Bill, who works on an 800-acre farm and used to own a bar/restaurant. His town is in Howard County, Iowa, which flipped by the highest percentage in the country. “The working guy is just tired of enabling people to do nothing, it boils down to economics, and it makes your blood boil when you pay your taxes and see how it was spent. There has not been any significant growth in Howard County at all.”

Enlarge

Vickie Ator, 61, the bartender at the local tavern, flipped to Trump after 40 years of voting for Democrats, in part because she couldn’t stand Clinton. She voted for Bernie Sanders in the primary. The guy she’s serving at the bar wrote Bernie in for the general election. “Nobody liked Hillary, so they went to Trump,” said Ator, who laments the town’s declining trajectory and reminisces about the John Deere plant that once was. It left about 45 years ago, confides the mayor.

Around the Mississippi River Valley, you taste, hear and see such sights of post-industrial America that are replicated hundreds of times across the clichéd ‘Rust Belt’ region of the United States. Although the populations are small (some towns have 34 voters), they symbolize the trend, where, from Iowa to Ohio to Pennsylvania to Michigan, white working class voters like Buehler and Ator switched their allegiance from the Chicago community organizer to the New York magnate, casting Trump as their latest populist superhero and channeling into him their seemingly never-ending thirst for “change,” a concept that they struggle to define but often boils down to economics, especially stagnant wages, job loss, Obamacare increases, and regulation.

If you line up the government maps for weekly wages in Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, the counties that flipped for Trump have some of the lowest numbers in their respective states despite a strong work ethic honed from farming. They are isolated places that not many move into, but some move out.

It’s easy to run into people working two or even three jobs; the pony-tailed waitress in her 50s serving warm apple pie that she had just baked at one Wisconsin diner in Crawford County says she makes $9 an hour, up from $7.50 some 30 years ago. Her boyfriend tried to get a job, but, as a result, they lost their FoodShare Wisconsin eligibility, making it not worth it.

The waitress said she would have favored Clinton but was too busy to vote and didn’t see the point of it besides. Her elderly mother, sitting next to her at the counter of the otherwise empty establishment, didn’t vote either, even though she lives next door to the polling place.

In Crawford and Howard, the weekly wage is under $650. Compare that to the wealthiest counties where folks make at least $200 per week more. Out here, you might have to drive 28 miles to the closest grocery store, cell phone service is hard to come by, colleges are few, and the nearest hospital may be a county away.

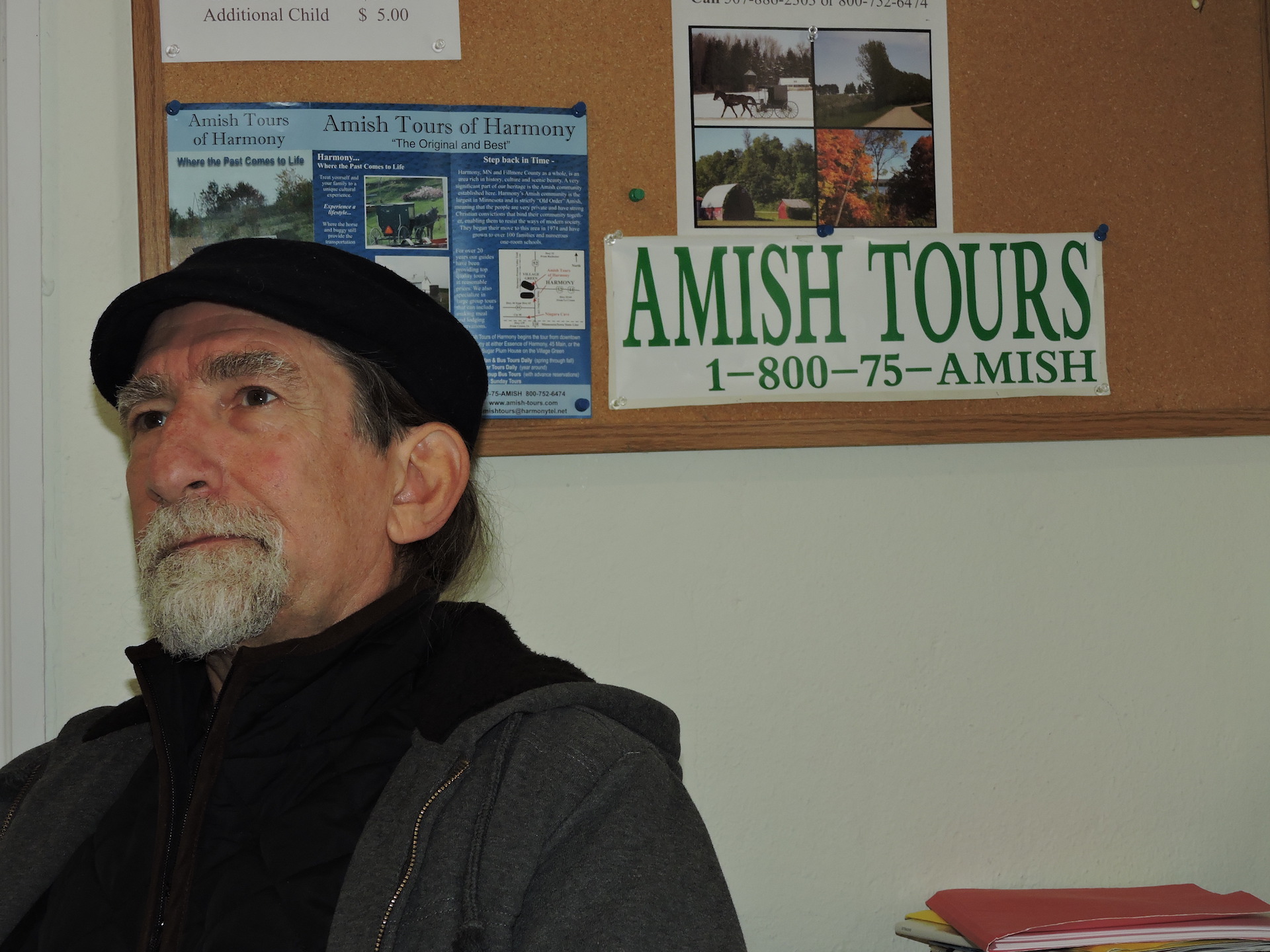

Up the road only a short distance, in Harmony, Minnesota, economic duress similarly dominates conversations. Reuben Hershberger, 51, a former member of the Amish Community and Trump voter who also once voted for Obama, pauses from selling wooden furniture to explain that his government healthcare premiums are jumping from $300 to $900 a month. Asked whether the Muslim refugee influx to Minnesota drove his vote (since Trump made a big deal of that), Hershberger says he’s fine with the Somali refugees in the state, “If they abide by the law and pay taxes.” He’s more interested in talking about jobs and wages.

Enlarge

As for Buehler, his affection for Trump also comes from a position very specific to his own life. “I am the Forgotten Man,” he says, echoing a Trump post-election tweet. He voted for Trump in part because he wants order back overseas, at the border, and in the cities. Prior to retirement, Buehler worked in a local factory that produced the vents put in Chicago’s Sears Tower before the factory moved to Mexico. He accompanies that story with a wave toward such a ceiling vent in his garage.

Now he stays in a garage that he’s converted into living quarters, with his TV spewing Fox News a few feet from his car, not far from a cross affixed to his wall and a sign making fun of Osama bin Laden. He also supported Trump because he felt that Trump would bring jobs—like his own—back from abroad. Like many of his neighbors, he’s a ticket splitter and independent voter. He left the U.S. Senate race spot on his ballot blank. Democrats might take future heart in the fact that it doesn’t seem like many of these people are firmly fixed in one partisan position. To them, Trump was appealing because he promised change that echoed the past. It was, ironically, hope that motivated them.

Asked what connects such different states, Buehler said it’s not the water that unites. “It’s the land.” The people of the region tend to work with their hands and stay connected to the earth, he says; they are farmers, deer hunters, loggers, and cement mixers.

Their towns are graying; their younger generations have gone. It’s a youth flight if you will (Census data backs this up as many of the communities have aged since 2012). In Lime Springs, Iowa, the woman with the Budweiser at the end of the bar is 93, and business has dropped because people are too old to go out much anymore. You can spend hours in some of these places without ever seeing a child. This area, with its scarce population and decaying infrastructure, looks sort of like Cuba, one student notes, frozen in the amber of the 50s, with economic advancement never arriving, although out here, people just want government to leave them alone.

Enlarge

The areas also tilt male. In Mabel, Minnesota, the kindergarten class has more than 20 boys and three girls. They are as white now as they were 100 years ago. Mabel has a working phone booth that can only make local calls, and the room where Charles Lindbergh slept in the downtown hotel looks virtually untouched (patrons are entrusted with the key to the lobby). The Somali refugees who have flooded into Minnesota are in Rochester, the big city (although the African-American man and woman pumping gas in small town Harmony, Minnesota say they’ve never faced racism in town).

These hamlets are time capsules of the past right down to the Viking statue honoring Norwegian ancestors in the middle of one of them, and histories of these villages tend to paint their economic high points as 1912.

It’s all the perfect petri dish for Trump with his rhetoric about making America great… again.

The Trump Triangle

If one were to travel the length of Madison’s ‘beltline’ far beyond city limits, that person would eventually reach Crawford County. Two hours from Madison, the Wisconsin state Capitol, three hours from Iowa City and four hours from Minneapolis, the county is in striking distance to many of the Midwest’s major cities, but it looks anything but. Nestled far away from clustered buildings and busy city streets, Crawford County is a land of dairy farms, deep valleys, and spacious country roads.

Within Crawford County is an area that might be dubbed the “Trump Triangle.”

It’s a set of five towns that flipped the most in the county that flipped among the most in the state, which is part of the region that flipped the most in the entire country percentage wise from Obama to Trump. The central point of this triangle (in geography, not in stature) is the town of Steuben, population 131 (at least six years ago). It flipped most in the state of any community. The maximum population of Steuben in the last 100 years hit 321 in 1940, a 22-percent increase from 1930. In 2012, about one-third of Steuben’s small population voted for Romney. In 2016, about two-thirds picked Trump (although in a town that small, the shift in numerical terms is about the size of two families.)

The town is 99.2 percent white and the other .8 is Native American. According to Bob Atkinson, a local bar owner there, the census number includes “Dogs, cats, and the kitchen sink.”

The road directly into Steuben is surrounded by low marshes and broken trees. The roads are curvy; the rock ledges go up high on the left side of the road as the Kickapoo River flows on the right. Ears of travelers’ pop on these winding roads that culminate in Steuben. The highway into town was sponsored by a gun silencer gun company, and there are signs for guided cave tours. The roads are lined with what seem like abandoned cars, but it’s just people out hunting. Forget trying to use GPS.

Small and isolated Steuben gets its name from Baron Friedrich von Steuben, a Prussian soldier who helped George Washington restore order at Valley Forge. One blog dubbed it among the top 10 Wisconsin small towns where you’d never want to live, saying it had 25 people per square mile.

But the people here are friendly and like the place. It’s a “good” place with “good” people, you hear again and again. This is where you find Jo Bunders, a grandmotherly woman who serves chili and burgers out of her family-owned tavern, Jo’s Kountry Bar (bars, churches, and high school sporting events are about the only communal activities around here, except for the ritual of hunting.)

Enlarge

“I personally vote for who I like. I’m independent, I voted for Obama twice, and I voted for Trump just because I’m sick of the politicians who are out for themselves,” Bunders says, as she serves a tavern-full of orange-clad deer hunters, many of whom rant against government and politicians but most of whom didn’t bother to vote (there’s a similar disenfranchisement, economic stress, and disconnect among non-voters in Milwaukee, as it turns out.)

Jody Martin, 56 is a semi driver and Jo’s patron who did not vote because he thought it doesn’t do any good. Martin could not recall the last time that he voted. Brian Haworth, 53, has been coming to town for 30 years from Green Bay to hunt. Brian and his son 23-year-old son, Josh, both did not vote. Brian was quick to remark that his wife voted “for the guy with the fake toupee.”

Josh said he had a gut feeling that Trump would win because so many people he knew liked him and because a lot of people criticized Obama. He said he didn’t vote because there wasn’t anyone good to vote for.

Bunders, a small business owner like many out here, said she had a strong reason to vote: Her Obamacare costs are going up by $86. That might not sound like a lot to some people, but it puts her monthly healthcare costs at an entire full week’s wages.

“I’m self-employed,” said Bunders, who lives in a county without a hospital. “That’s one week’s pay check. Literally out of pocket.”

Steuben, like the rest of the triangle (or maybe it’s more of a pyramid with Steuben in the middle) is an intimate community where people skew old and know each other’s names and the names of each other’s dogs. There are two establishments in town, both bars, and both owned by middle-aged women with male sounding names, Jo and Lou. You might think women in non-traditional fields might favor Clinton, but Jo and Lou diverged: Jo went Trump, and Lou stuck with Hillary Clinton (the female bar owner in Lime Springs, Iowa, says she wants a female president, just a different one.)

Jo, who is also the town clerk, reveals that there used to be a post office in Steuben a few years ago, but a flood closed it for good. There was a factory in nearby Boscobel that lots of people worked at until a few years ago, when it moved overseas. Steuben remains so white that Jo can name the only non-white people off the top of her head (African-American boys who live with their mother down the road, a woman who never seems to be home.)

Race doesn’t come up first here, although the media have focused on it. The media felt that the sexual assault allegations and the Billy Bush tapes would be a big deal with the people…the media got that wrong too. The media thought that Clinton would win in a landslide…and obviously, the media got it wrong. Sensing a theme, here? The people of the Mississippi River Valley didn’t trust the media and felt ignored by it. Guess who got the last laugh? Not the media.

Bunders was one of those voters who seemed unbothered by Trump’s sex talk. She said that a lot of “misogynist sh-t” happens at her bar. She didn’t bring up race until she was asked about it, but when she was, she was candid.

Racial mentions are most likely broached only when an interviewer digs into the topic. When you dig further, many offer nuances. They might support Trump’s wall, for example, but they don’t want all illegal immigrants kicked out, just those who commit crimes. They don’t want all Muslims banned, just those who are terrorists. They’re unhappy with unrest in America cities, but they didn’t like anti Scott Walker union protests, either, even though some of them were union workers years ago… when they were also Democrats. They pop out a few comments that raise eyebrows, though.

Enlarge

Bunders is bothered by people who are in the United States illegally, not all immigrants. She said they need to do the paperwork and become citizens. Bunders believes that we do need those immigrants, though. “I’m not going to pick apples, tomatoes,” she said.

However, she focused on economics and change.

“Because he’s not a politician,” Bunders said of Trump, when asked to boil down why she liked him. “He’s just a businessman who started small, just a businessman and a regular person looks at that. He talked a lot of sh–t the first year, and he’d have a good week and then say something stupid, and I would think, ‘Oh my God,’ but the last month maybe of the candidacy, he really looked in the camera and looked like he was talking right at you.”

It may have been marketing savvy, but Trump managed to capture the “voice” of these people, in a way that made them feel like he was speaking authentically and to them directly, perhaps on the next bar stool over.

Bunders introduced a new theme that became part of the lexicon:The idea that Trump was the best option of two less than desirable choices. Some people were not completely sold on Trump, although they were sold on the idea of an outsider. However, Hillary they hated. Her emails did matter to them, but they felt that way before James Comey.

“People are just looking for change, something different than a politician,” Bunders added. “When I talk to people, he was the lesser of two evils. People were not impressed at all with Benghazi and the emails.”

From the doors of Jo’s, one can see Lou’s, the other establishment in town. In a county more populated by men, two powerful women own the city’s two taverns. The owner, Lou Atkinson, is the namesake of Steuben’s other business. There’s a watermark on the light post outside Lou’s R&R, where the Kickapoo River was once eight feet high, flooding the bar in 2007. Both Jo and Lou have run their bars for more than three decades.

“A lot of people who I don’t normally see voting voted,” Atkinson said. “An older, ‘redneck’ sort of crowd turned up for the election…People around here like what he [Donald Trump] says…They like the message he’s trying to put across.”

Lou has thick gray hair that used to be black. It’s pulled back into a ponytail because she’s preparing meat for prime rib night at Lou’s R&R, the bar she’s owned for almost 30 years, since, as a single mother with kids, she came to Steuben, Wisconsin. She’s thin and taller than most other people in their 60s. Atkinson has intense, wise eyes that contrast with her reserved demeanor.

Atkinson is a sort of town ambassador. She knows everyone who traverses the threshold. The place is so informal that a customer who grew up in town goes behind the bar to prepare her own drink. Lou’s husband, Bob Atkinson, who is of German/English/Norwegian descent, greeted everyone who came into the bar by name. He grew up four miles away on a farm. The Atkinsons live above the bar. Lou voted for Clinton, and Atkinson voted for all other offices but president, explaining, “There’s an old saying: we have to pick between a crook or a liar, but which is which?”

They missed the Obamacare cutoff by 30 bucks and now have a huge monthly amount to pay for their health care that they don’t even use.

Enlarge

A patron, Sheryl Groom, came into the bar ranting about Hillary. She suggested everyone read the emails and said people shouldn’t listen to the media. She believes television stations practice mind control. Another customer, Ted Groom, called Steuben and its neighboring villages “a quiet, little area to raise a family.” He was upset about Trump’s comments toward women, and voted Democratic, but he felt that others around town didn’t like Clinton and Obama’s comments on gun control.

Indeed, many of those sitting in both bars were hunters clad in orange for the first day of deer hunting (at Lou’s, there was a gun raffle going on too). They eat what they kill around here (one hunter who came into the bar said he’d shot the deer that had been turned into the venison jerky for sale there), and they don’t take kindly to people wanting to regulate their guns. They have that luxury because the areas are safe enough that you rarely see a cop and the local Sheriff’s Department advises one broken down motorist to leave her keys on the front seat with the car unlocked and a note for the tow truck driver.

But the hunters tend to bring up the economy before guns too. “Even though he (Trump) is bat sh-t crazy, hopefully he’ll fix the economy,” said one of the local hunters, Tim Bray, as he walked up to the highway down the road from Steuben, leaving his deer where he shot it. Bray flipped from Obama to Trump.

Lange, 86, is another Trump voter who epitomizes the close-knit aging nature of Steuben. Lange lives just down the road from Jo’s and Lou’s, literally surrounded by the past in a trailer near a shed that holds what can only be summarized as “stuff” he’s salvaged for decades from the town dump. He frequently visits Jo’s bar, especially for the early morning coffee klatsch (it’s the only place you can get coffee in the morning in several neighboring Trump Triangle towns). He and Jo were exuberant on election day and didn’t try to hide it.

Old gun magazines, toilet seats, and, most dramatically, the skeleton of an airplane, clutter the garage. Outside, a cow wanders around.

“Well, we all go down to Jo’s every morning for coffee with the boys,” Lange said from his trailer filled with what are now artifacts, but which – in Lange’s glory years – were modern technology. “I’m the oldest one but there’s a bunch that ain’t (sic) too far behind me.”

Enlarge

Lange moved to Steuben from Oconomowoc in the Milwaukee metropolitan area in the 1970s when the “yuppies” moved in. He recalls seeing a black man in town years ago but can’t quite remember his name. He was upset when he saw two Muslim women in the Walmart one day recently (it’s many miles away).

“The other day I was at Walmart, and I was walking down the aisle, and I turned around and there were three women – Muslim, I assume – dressed in all black,” Lange says, gesturing his hands from head to toe. “It took me back; I jumped. I have nothing against the Muslims, except, when they come to this country, I assume and expect them to assimilate to our society.”

He gets his news from an underground newspaper. When he inevitably says he voted for Trump because he wants change, he struggles to define what that means, but it becomes clear it’s a regressive change and, although he doesn’t spend much time on race, there’s some latent coding. He wants the way it used to be, at least for him. He keeps referencing American culture, and it becomes clear that, to him, that means Christian. He seems to skip over the negatives of the past – Jim Crow and so forth – by focusing on how it was better for him, economically.

“America was great in the 50’s,” Lange continued. “I was making $15 an hour; gas was only 27 cents. I want to get back to that.”

Lange also addressed the economic stress in Steuben today.

“If you look in the paper, you’re not looking at romantic jobs,” said Lange. “They’re drudgery jobs. Who wants to milk cows for a living, or farm work, or drive trucks or something like that? Not many people.”

Lange agrees that the village of Steuben is getting older.

“Young kids want the city life; I can’t blame them,” he said. “I was born and raised in the city, and I wanted the country. They just have the opposite frame of mind.”

He didn’t care about Trump’s sex talk. “It’s locker talk, I’ve been there – I know how guys talk when they are supposedly not being heard,” Lange chuckled.

From Lange’s trailer, the students decided to head to an outlier in the Triangle – Gays Mills, a town that stuck with Clinton a few miles away. Rumors flew that a commune existed near town, and the first thing you see are the apples on the signs (the fruit is the town theme) and a natural food store.

Enlarge

It turns out that Gays Mills is more female than the rest of Crawford, younger, and slightly more diverse, although that’s not saying much, but it is interesting in light of its Clinton tilt. The other way it differs from the towns around it: Lots of outsiders come in every fall to pick the apples in its organic orchards.

No one driving through the dreary, dark hillside north of Gays Mills, wishes for any technical problems on the road. But when the brakes fail entirely around 9 p.m. on a cool, Saturday night, anyone would love for someone who lives in the shadows of Crawford County to materialize next to their car.

Carlos Tinoco, 33, walked up to see what was wrong. The travelers had been following the loose rumors about a hippie commune called ‘Star Valley’ from the Gays Mills downtown area.

Tinoco quickly debunked the town’s folklore. He also revealed that he has been an employee at the farm Star Valley Flowers in nearby Soldier’s Grove for 14 years since he first came to the states illegally from Mexico.

According to statistics, 81.9 percent of the population in the Gays Mills area is of white descent while 6.6 percent are African American and another 6.6 percent are Hispanic. That might not sound like a lot of diversity, but, compared to surrounding towns, it is. Tinoco, who is Latino, says he can’t vote.

What’s it like to be non-white in such a white area? Tinoco said he has not experienced any racism while living in the county, although his daughter is worried about what will happen to her parents with Trump now in office.

Enlarge

From Steuben and Gays Mills, one ventures down the rolling hills of Highway 26 to Prairie Du Chien—the big city of the county. It’s about a 25-minute drive. Although the population difference between Steuben and Prairie du Chien is roughly 6,000, the sentiments among the people were similar. The town’s population has almost 600 veterans. It is 93 percent white. Prairie du Chien is Wisconsin’s second oldest town and was known for being the center of French fur trading.

Donlon, the Betty White write-in voter, stands at the back of Bob’s Bar on the main strip, Blackhawk Avenue, of Prairie du Chien. She expresses distrust in the media. Throughout the weekend, across the states, this theme returned quite often.

Donlon grew up in a small Iowa town, but she went away and earned a four-year degree from Iowa State University in Ames. Donlon has the unique perspective of being from a small town, living in a bigger town (Prairie du Chien) and attending a large university that, with 36,000 attendees, is six times bigger than Prairie du Chien and many times larger than her original hometown.

“Have they even seen cows?” Donlon, a dairy farmer, said of the national news media. “Corn, milk and beef prices are too low. It is horrible. Farmers are not making ends meet.”

Michael Paul Steven Jacobs works in a prison nearby that is filled with inmates from Milwaukee. He repeatedly insisted that Clinton was a crook when he joined the conversation. He despised Clinton, announcing that he was “Tired of Hillary’s little b-tch as-. She should have been indicted. If we did that we would be in prison. She has enough to bury her.” It makes one wonder if a different Democrat, say Joe Biden, could have retained these voters.

Jacobs felt that Bernie Sanders appealed to a lot of voters who think the system is “rigged” and switched to Trump (especially as Sanders tagged Clinton for months as a corporate elite insider making money off Goldman Sachs speeches). Jacobs also thinks the system is “rigged.” Many people repeated Trump’s endlessly repeated and boiled-down phrases. They all knew them. Hillary was a criminal. The system was rigged. Make America great again. Drain the swamp.

But Jacobs also added, returning to the underlying refrain: “People are tired. Milk farmers are not making any money.”

Iowa Beckons

From Prairie du Chien, it takes five minutes to reach Marquette, Iowa. Although the journey is short, it seems to be a journey through time rather than simply down West Iowa Road. Marquette and its sister city McGregor resemble a West Virginia mining town of the 1850s.

The rolling, developing bluffs that the town is dug into play the role of the Appalachian Mountains that form the old mining towns up and down its axis. The buildings are brick, symmetrical, similar in height and close enough to touch. The main street, so named, is long and straight but elevates up and down with the varying gradient of the land.

From Marquette-McGregor, the students traveled to Lime Springs, Iowa, a mostly flat and barren drive, although along the way was an Iowan farm field with two Trump signs stuck into bales of hay. The town of Lime Springs – located in the county that flipped by the highest percentage to Trump in the nation – itself was depressing, at least on a Sunday night. There were few cars, few establishments and even fewer humans. The ones who were reachable had plenty to say.

Ator, 61, the bartender who’d switched to Trump after 40 years of voting for Democrats, owns KCD’s in Lime Springs. She is a strong and notable. Trump was the first Republican candidate this former welder and farmer ever voted for. The only other businesses apparent on the Main Street were another bar (closed) and an antique store. The town stands in the shadow of granaries. The average age of the patrons in her bar that Sunday night seemed to hover around 80.

Enlarge

Ator felt that both candidates “sucked” but voted for Trump because he seemed more authentic than Clinton. She also swooned to the Trump tune because Lime Springs has seen its fair share of jobs head overseas. Ator said the town used to buzz, and streets used to be packed. In the past, it was difficult to find a parking spot for a car; today, it is difficult to find a car for the parking spots.

“This used to be a booming town to grow up in. You couldn’t find a place to park in Lime Springs because it was so busy and wild,” said Ator.

Lime Springs was named after a spring that continues to produce fresh water today. Most of the jobs in town are related to agriculture. The historical site of the Lidtke Mill is known for its buckwheat flour that used to provide 100 barrels of flour a day. Besides being known for agriculture, Welsh heritage is deeply seeded in the community in an otherwise Norwegian and German region.

“There has not been any significant growth in Howard County at all,” said Mayor Bill.

Howard County’s population estimate was 9,410 in 2015. The unemployment rate has declined since Obama’s two terms in office (that’s true also in some of the other counties in the project), yet Howard County also has one of the lowest weekly wages in the entire state, averaging about $642 a week, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The Labor force is increasing as the wages are continuing to stay low. If there are more jobs, people aren’t making very much at them.

Why did she switch to Trump? “Number one, he isn’t into politics,” Ator said of Trump, echoing the mistrust of the “establishment” and government also found in the other states. She sounded a lot like Bunders, one state over. “He used his own money. Nobody could bribe him.”

She added, “How can I be called a racist for voting for Trump when I voted for Obama?”

Enlarge

Michelle Stockman, 36, sat on her porch not far from the bar smoking a cigarette while her daughter stood behind the screen door. She had short blond hair and wore a dark hoodie. At first she was very hesitant to talk about politics and said “I don’t know” frequently. Eventually, she grew comfortable and said she voted for Donald Trump.

“At least he’s not a criminal,” Stockman said.

Stockman lives on Willard Street in Lime Springs, Iowa. It was quiet that Sunday evening. Many people were in their houses, hiding away from the chilling weather. The small dog next door to Stockman was chained outside barking happily at passersby.

Stockman previously voted for President Obama. She also liked Michelle Obama and Bernie Sanders.

In reaction to accusations that Trump supporters are all racist bigots, she said that is false, and people who think that are the bigots.

Trump’s comments about women did not bother her.

“I’ve worked with men and they’re all like that,” said Stockman, who works for Dr. Pepper.

Stockman thought that Trump’s phrase, “Make America Great Again” was dumb. Her 16-year-old daughter wore a hat with the phrase, and Stockman told her to take it off. She didn’t want her daughter to get harassed.

She also didn’t like the protests after Trump had won. “A lot of people in their 20s don’t know how to take rejection,” said Stockman. There were no specific policies that Trump and Clinton talked about that Stockman thought were important.

“I didn’t give a sh-t, I went to go to bed,” said Stockman about election night. She said the election was like a T.V show.

Stockman’s neighbor, Todd Mensink, 40, came out of his home in a hoodie and plaid pajama pants. He shivered a bit as he held a cigarette between his fingers.

Mensink is a sociology and criminology professor at the University of Iowa. He voted for Jill Stein this year and in 2012. Mensink did vote for Obama in 2008. He listens to both Minnesota Public Radio and Rush Limbaugh.

“Do you keep voting for the lesser of two evils or take a stand?” Mensink said.

Amish Country

About a half hour north from Iowa, on the way into the small town of Harmony, Minnesota, the click clack of an Amish horse drawn carriage can be heard as it makes its way into town. The downtown strip is peppered with wooden hand carved statues that are Norwegian themed, yet, oddly resemble gnomes. On a Sunday afternoon, purple Vikings jerseys are visible through the store fronts and bar windows. The further north you go, the more Scandinavian it all looks, right down to the early Christmas decorations.

While some Harmony natives were out and about Sunday grocery shopping, the heart of the neighborhood was mostly still, although some residents were out tidying their lawns in preparation for the harsh Minnesota winter (or in neighboring Mabel, they were in the local school gymnasium playing Bingo).

Fraying infrastructure and all that associates with it was replaced by something more bustling and refined. The streets were newer, clean, well paved and recently painted. When one travels laterally off the main-strip of southern Minnesota hamlets into the residential areas, one sees manicured lawns. However, the wage maps show a similar story to the rest: This county, Fillmore, like Crawford and Howard before it, hosts some of the lowest weekly wages in its state. And it flipped dramatically to Trump (although Trump made Minnesota far more competitive than anyone expected, he did lose that state).

A history of Harmony says it used to be an important trading point in southern Minnesota for corn and grain. It had a litany of businesses back then, including a rolling mill, lumber yard, and “three general stores which are also important enough to deserve the name of department stores,” says the history. It was also known for its “moral and progressive spirit,” says the article.

What the people of Southern Minnesota expressed about the election was nearly identical to that of their Wisconsin and Iowan neighbors.

Robert David-Schmidt invited a couple of reporters into his garage, a garage whose centerpiece was the bloody corpse of a deer, a fresh kill. Before approaching the garage, Schmidt introduced the trio to “Captain Little,” the man’s semi-truck he uses for work as a trucker. He is the quintessential hard-nosed “rub some dirt on it” American. He voted for Trump and has voted Republican all his life.

Enlarge

“I was happy with the outcome, but not with how the other side took it,” Schmidt said. “Black lives matter changed it. What’re they whining about? What do they want?”

He also continued the narrative regarding national news and how the pre-election projections focused on the urban areas and avoided the common man.

“Media ran the election,” Schmidt said. “Twin cities are heavy blue…you need to go to small places.”

A few blocks away, some of the group sat down with Reuben Hershberger, the former Amish man with the wood furniture store. He was shunned by the Amish community in Harmony just down the road for leaving it, and now must travel to Ohio to refurnish his furniture store. The students were directed to him by an anguished Amish tour guide, Rich Bishop, 66, who voted for Clinton and informed them about Trump voters, “There’s a group of people who are very reactionary. (Democrats) didn’t emphasize how well America was doing now, and we didn’t need to make America great again. I didn’t believe people were so uninformed.” He thinks education matters and that too many people in these areas are limited educationally, not only when it comes to college but also travel.

Cleaning his hands off with a nearby rag, Hershberger, 51, takes time out of his day at work to talk with students about his Amish upbringing and thoughts on the election.

Hershberger grew up Amish but left the community when he was 18. Despite his father being the bishop, Hershberger expressed that religion in the Amish community was unappealing. The church oversees telling you how to live and what you can and can’t do (another former Amish woman down the road tells the students she asked God to put the right person to vote for into her head. She ended up not voting). The area is largely filled with Lutheran and other churches; the Old Order Amish in the area are separatist from the already isolated community and most don’t vote.

Amish are also required to pray eight times a day, not wear bright clothing, wear hair a certain way and have clothing be a certain length. In the Amish community, the church takes the role of the government.

Enlarge

Wearing a beige colored jacket with his name embroidered into it with navy blue thread, Hershberger stepped out of his small office that was filled with papers of furniture orders hanging on the walls. Standing in front of the furniture products that are painstakingly made by his Amish friends, Hershberger told the students that he voted for Obama in 2008. Hershberger voted Obama for the change that he promised. After not seeing the change that he wanted, he voted for Romney in 2012.

Living in Fillmore county, which flipped from Obama to Trump, Hershberger said he and a lot of his friends voted Trump. While Hershberger said he has no problem with a woman being president, he has a hard time believing Hillary Clinton would commit to her promises – a trust issue that could stem back to his trust in Obama for change and his subsequent letdown when he felt he didn’t see enough.

Still wanting to see a change, which he defines as largely economic, Hershberger voted for Trump because he wanted to see something different since Trump is a businessman. Hershberger does not want to be so dependent on the government.

While Hershberger did say that he wants the government to be stricter on letting people into the United States, he isn’t opposed to letting immigrants in. He thinks deporting so many people wouldn’t be a good thing for the country.

“We’re all from different nations; I don’t think we should keep them out,” said Reuben. “If we send them back, who would take their jobs?”

Hershberger still has the faint look of the Amish. His blond hair dangles past his ears. His baseball cap has a fish on it. He doesn’t think he was uninformed; he just preferred Trump. He didn’t mind a woman being president, just not Hillary. He and many of his friends voted for Trump. The Old Order Amish community he left seems just a few notches more separatist than the other anti-government folks in these areas.

Minnesota is wrestling with the fourth-highest Obamacare premium increases in the country (thrust on them in late October, right before the election), leading even the Democratic governor there to call it unaffordable. And don’t forget it’s a state that once elected a wrestler as governor. Hershberger highlights his large premium increase ($600 a month, a lot for a small businessman).

Enlarge

In nearby Mabel, Minnesota, it’s also easy to find Trump voters, even though the state hasn’t voted Republican since 1972.

Its quaint main street has a post office, American Legion, barber and a liquor store. Named for a railroad man’s daughter, the town’s website says it was quite thriving – more than 100 years ago. “In 1912 thriving businesses lined both sides of Main Street for two blocks,” says the site. On nights after around 9 p.m. now, the town falls deadly silent and the headlights of cars are seldom seen. There is one restaurant that feeds the town’s appetite for food and drink, but also entertainment. The Highway 44 Bar & Grill, beyond normal restaurant amenities, hosts concerts and meat raffles. There, the group met a man who prides himself for being off the grid.

Ron Gerard is 60 and was having breakfast before a day of hunting. He voted for Trump.

“I’m not in a city,” said Gerard, clad in orange. He sat next to a friend from Alaska, and it was hard not to see the similarity.

“I’m not around people all the time. I’m here where I am alone. It’s slower. I can think for a little bit. We don’t have 6 million people like New York City. We are all rural. A lot of these people that live in cities are sheep. They don’t have a mind of their own.”

Gerard maintains his privacy and individuality. He doesn’t use ATM’s, does not have a credit card, doesn’t own a smartphone or computer, and does not use the internet. He says he hasn’t used email for 25 years, oblivious to the fact that it didn’t yet exist.

“Politicians are in it for the money,” said Gerard, sounding exactly like an echo of his neighbors in the nearby states.

“Everybody in the country is against politicians,” he concludes.

“I just don’t care for politicians at all.”

-This story was written by Keaton Walkowski, with reporting from the UWM reporting team, including Jordan Garcia, Sabrina Johnkins, Brandon Anderegg, Nicole Frechette, Jenna Gaidosh, Ana Martinez-Ortiz, Christina Luick, Madison Goldbeck, Kaliice Waker, Nyesha Stone, Aubryana Bowen, Jenna Daroszewski.